An early 13th-century-AD (likely biased) depiction of the 'pagan' Irish kingship ceremony, during which the king bathed in the blood of a mare before sharing the meat with his courtiers. From Topographia Hibernica by Giraldus Cambrensis. Credit: British Library Royal MS 13 B. VIII f. 28v; reproduced under Creative Commons license CC0 1.0

Archaeological analysis of horse remains from medieval Hungary indicates people continued to eat horses long after the country's conversion to Christianity, suggesting the decline in horsemeat consumption (hippophagy) in the region was not for religious reasons, questioning the prevailing historical narrative.

Horsemeat consumption, once common in pre-Christian Europe, declined over the course of the Middle Ages. Written sources indicate that this was tied to the adoption of Christianity.

While the consumption of horsemeat was never officially forbidden by the Church, many medieval Christian sources described it as impure and linked it to the "barbaric" practices of non-Christian peoples.

"Based on documentary sources, abandoning horsemeat consumption is widely associated with the emergence of Christianity in medieval Europe," state the authors of the research. "However, in the absence of an explicit prohibition (comparable to the ban on pork in Judaism/Islam), a great degree of regional diversity is apparent in the condemnation of horsemeat across Europe."

Despite this uncertainty, a large-scale archaeological survey of horsemeat consumption in medieval Europe had never been performed. Therefore, the historical narrative that Christianity made hippophagy taboo had largely been uncritically accepted.

To tackle this, Professor L�szl� Bartosiewicz from Stockholm University and Dr. Erika G�l, senior researcher from the HUN-REN Research Center for the Humanities in Hungary, examined horse bones from 198 settlements across medieval Hungary to determine how horse consumption changed over time. Their results are published in the journal Antiquity.

By analyzing the percentage of horse remains in these refuse contexts, they were able to calculate whether a site had a greater-than-average amount of horse remains, indicating horses were being eaten there.

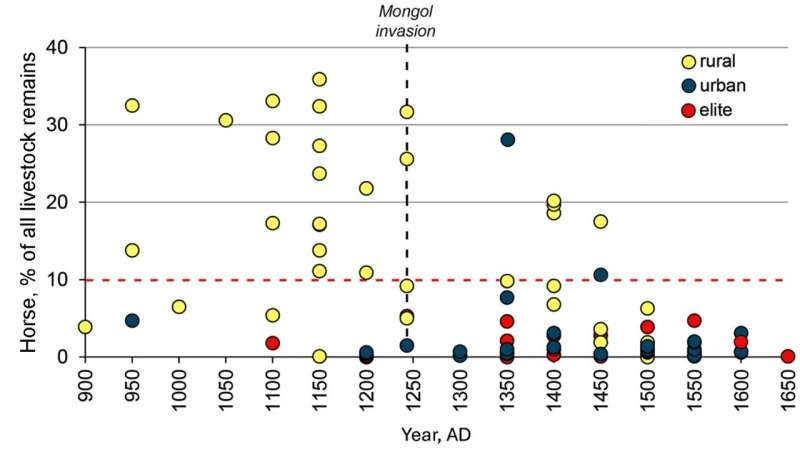

Changes in the percentage of horse remains by settlement type in assemblages numbering more than 500 bones of livestock. Credit: Antiquity. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10138

The authors found that the percentage of horse remains in refuse pits is relatively high, indicating people were still eating horses more than 200 years after Hungary's conversion to Christianity in AD 1000. Especially at some rural sites, horse bones made up as much as one third of the identifiable remains of livestock in the food refuse.

However, horse consumption began to decrease following the Mongol invasion of 124142. This was likely because horses became scarcer and more prestigious.

"Horses were valuable war booty and surviving horse stock was probably in high demand for purposes other than food," explain the authors.

Furthermore, the Mongol invasion killed 40%50% of Hungary's population and, to re-populate the country, the Hungarian king invited people from the west to settle.

Unlike Hungary's previous, largely pastoralist population, these incoming groups were more urbanized, and horsemeat was not part of their dietary tradition. They preferred pork, as pigs are more suited to sedentary farming.

Overall, Bartosiewicz and G�l's findings indicate horsemeat consumption declined as a result of the decreasing accessibility of horsemeat and the demographic changes in Hungary's population associated with the impact of the Mongols, not spiritual factors.

They also show the value of archaeology in questioning historical narratives, which are often written long after the fact and with their own agendas.

"Tropes equating hippophagy with 'barbarity' have abounded since antiquity," conclude the authors. "This othering is most poignant in sources that post-date the events they are describing, sometimes by centuries, and possibly portray negative generalizations rather than past 'reality.'

"The contribution of horse remains to food refuse correlates with general historical trends but needs to be understood in light of the complex interactions between different peoples and their physical and political environments."

More information: L�szl� Bartosiewicz and Erika G�l, Hippophagy in medieval Hungary: a quantitative analysis, Antiquity (2025). doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2025.10138

Journal information: Antiquity