The plant, owned by the utility giant AES, has long plagued this part of Puerto Rico with air and water pollution. During Hurricane Maria in 2017, powerful winds and rain swept the unsecured piletowering more than 12 stories highout into the ocean and the surrounding area. Though the company had moved millions of tons of ash around Puerto Rico to be used in construction and landfill, much of it had stayed in Guayama, according to a 2018 investigation by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, a nonprofit investigative newsroom. Last October, AES settled with the US Environmental Protection Agency over alleged violations of groundwater rules, including failure to properly monitor wells and notify the public about significant pollution levels.

Governor Jenniffer Gonz�lez-Col�n has signed a new law rolling back the islands clean-energy statute, completely eliminating its initial goal of 40% renewables by 2025.

Between 1990 and 2000before the coal plant openedGuayama had on average just over 103 cancer cases per year. In 2003, the year after the plant opened, the number of cancer cases in the municipality surged by 50%, to 167. In 2022, the most recent year with available data in Puerto Ricos central cancer registry, cases hit a new high of 209a more than 88% increase from the year AES started burning coal. A study by University of Puerto Rico researchers found cancer, heart disease, and respiratory illnesses on the rise in the area. They suggested that proximity to the coal plant may be to blame, describing the operation, emissions, and handling of coal ash from the company as a case of environmental injustice.

Seemingly everyone Su�rez V�zquez knows has some kind of health problem. Nearly every house on her street has someone whos sick, she told me. Her best friend, who grew up down the block, died of cancer a year ago, aged 55. Her mother has survived 15 heart attacks. Her own lungs are so damaged she requires a breathing machine to sleep at night, and she was forced to quit her job at a nearby pharmaceutical factory because she could no longer make it up and down the stairs without gasping for air.

When we met in her living room one sunny March afternoon, she had just returned from two weeks in the hospital, where doctors were treating her for lung inflammation.

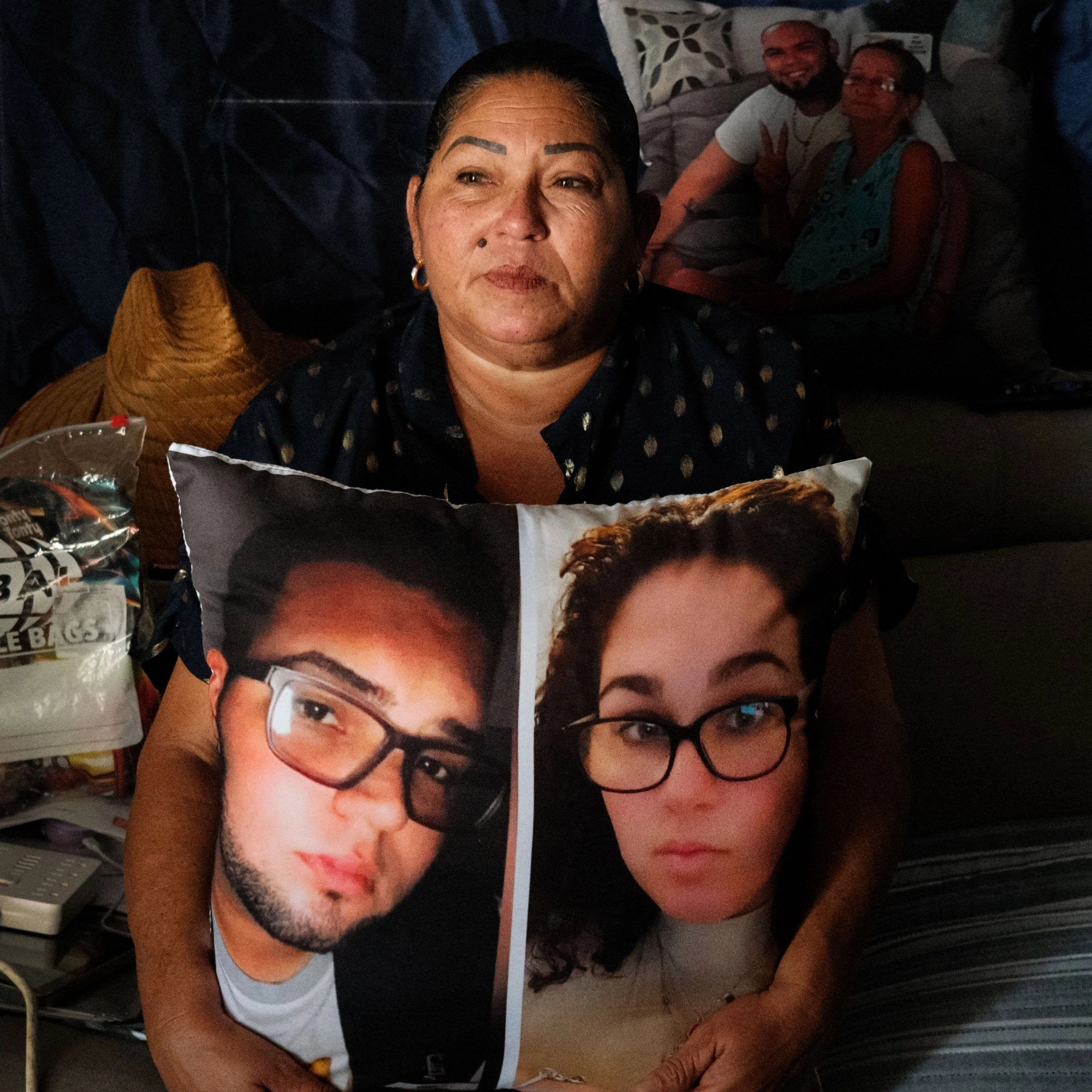

In one community, we have so many cases of cancer, respiratory problems, and heart disease, she said, her voice cracking as tears filled her eyes and she clutched a pillow on which a photo of Edgardos face was printed. Its disgraceful.

Neighbors have helped her install solar panels and batteries on the roof of her home, helping to offset the cost of running her air conditioner, purifier, and breathing machine. They also allow the devices to operate even when the grid goes downas it still does multiple times a week, nearly eight years after Hurricane Maria laid waste to Puerto Ricos electrical infrastructure.

Carmen Su�rez V�zquez clutches a pillow with a portraits of her daughter and late son Edgardo. When this photograph was taken, she had just been released from the hospital, where she underwent treatment for lung inflammation.

Carmen Su�rez V�zquez clutches a pillow with a portraits of her daughter and late son Edgardo. When this photograph was taken, she had just been released from the hospital, where she underwent treatment for lung inflammation.

Su�rez V�zquez had hoped that relief would be on the way by now. That the billions of dollars Congress designated for fixing the islands infrastructure would have made solar panels ubiquitous. That AESs coal plant, which for nearly a quarter century has supplied up to 20% of the old, faulty electrical grids power, would be near its endits closure had been set for late 2027. That the Caribbeans first virtual power planta decentralized network of solar panels and batteries that could be remotely tapped into and used to balance the grid like a centralized fuel-burning stationwould be well on its way to establishing a new model for the troubled island.